In the early years of the aught decade, Dan Solove, then assistant professor of law at Seton Hall Law School presaged that the new paradigm for privacy in the Internet age wasn’t George Orwell’s 1984 but rather Franz Kafka’s The Trial. In the book, the protagonist is subject to a secret trial in which he knows not the charges against him or the evidence used. He is not allowed to participate in the proceedings or dispute the evidence. In the end, the character is executed having never learned what the charges were. A few years later when Professor Solove developed his taxonomy of privacy, which categorized cognizable privacy violations, this form of privacy violation became known as Exclusion: the use of information about an individual without the individual’s knowledge or ability to participate. Solove’s taxonomy encompasses 17 distinct privacy violations spanning four broad categories: information collection, information processing, information dissemination and the non-information privacy issues in invasion. Exclusion is a particularly pernicious violation because it combines two fundamental forces that underlie many issues around privacy, namely imbalance in information and imbalance in power between the organization and the individual. In The Trial, the government is the perpetrator of this type of violation. Historically, government actors is where one mostly find this because government’s power monopoly prevents individual choice and the impact, such as loss of liberty, can be devastating. The unfairness of exclusion was crucial in criticisms of the US government’s no-fly list, which contained names of individuals who didn’t know they were on the list, even once known were unable to know or dispute the information used against them. Concern over exclusion also underpins the original formation of the Fair Information Practices (which was primarily aimed at government databases in the 1970s) to prevent secret databases to which individual couldn’t dispute inaccuracies. In the commercial realm, these concepts first took hold in credit reporting industry and the Fair Credit Reporting Act’s requirement for transparency and a dispute mechanism.

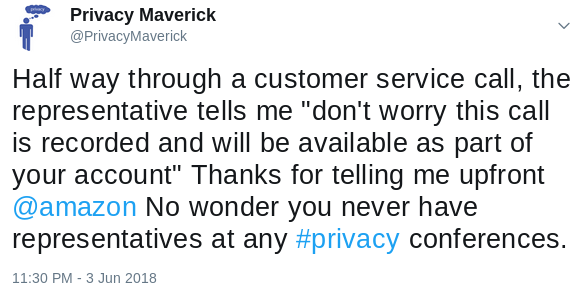

I’m a heavy user of Professor Solove’s taxonomy in my privacy by design training because it help participants categorize different types of privacy violations. It highlights, for most participants, that insecurity of data (which seems to be almost a fetishistic focus for many) is really only the tip of the privacy iceberg. I like to joke in my training that I’ve had every single privacy violation foisted on me in some fashion or another. Using anecdotes helps my students relate to the violations in a way that defining and explaining doesn’t. Personal stories convey even more than sensational news stories can. In one instance, I talk about how a cashier at fast food restaurant identified my then girlfriend to send her a Facebook friend request. I show students an Asian dating website where my picture was appropriated in advertising. Exclusion really hits home when I ask students if they’ve ever been put on hold and told their call will be answered by the next available operator. I discuss how some companies use secret profiles of their “problem” customers to constantly kick them to the back of the queue without the customer being able to know or dispute this status.

My most recent example comes from Amazon and is detailed below.

Last month I was traveling in Europe to attend a few privacy related events and conduct some training for Deloitte Romania. In Bucharest, I taught a CIPT course as well as my Privacy by Design class, relabeled Data Protection by Design for the EU audience. While in Romania I attempted to place an order on Amazon for an electronic gift card. Apparently this raised red flags within Amazon’s systems (an electronic gift card ordered by an American consumer but from Romania, which they probably inferred from my IP address). The order was canceled. Amazon also blocked access to my account for 5 hours.

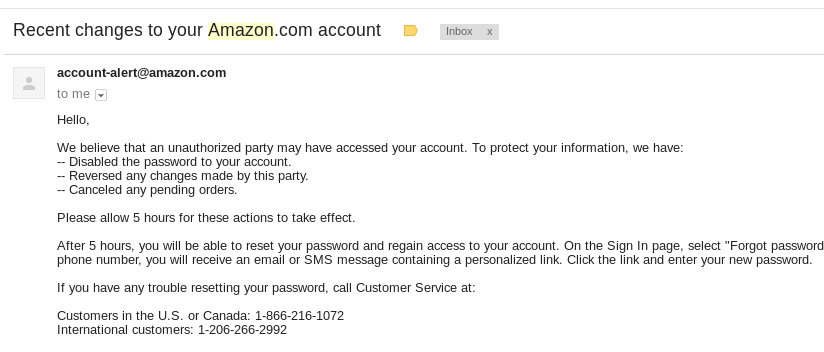

After 5 hours, I followed the instructions, which included resetting my password. I was back in and figuring it was safe since I re-authenticated my access to my email, re-placed my order . Of course, it wasn’t. Amazon repeated it’s effort but this time required that I call to reinstate my account.

I called Amazon, spoke with a customer service agent and after answering quite a few questions (like how long I had had my Amazon account, whether I had any linked devices, etc.), my account access was reinstated and I was able to reset my password and log in. I decided NOT to try and replace my order until I returned to the US the follow week, which I did. At this point my order went through and I thought everything was behind me. I even subsequently ordered Woody Hartzog’s new book Privacy’s Blueprint, without issue. [Side note, excellent book, highly recommended, just don’t order it from Amazon ;-)]

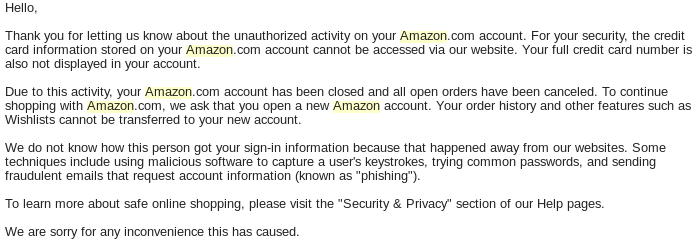

About two weeks later I’m in D.C. attending the Privacy Law Scholar’s Conference and ordered a present for a friend off their wish-list. BAM! My account was again shutdown. I didn’t realize it, since I was off doing actual work, but when I tried to check the status of the order I realized that they had shut my account down again. I called customer service but the best they could offer was to submit an email to the “Account Specialist” team. At 1:30 AM later than morning I received the following email:

Thank you for letting us know about the unauthorized activity on your Amazon.com account. For your security, the credit card information stored on your Amazon.com account cannot be accessed via our website. Your full credit card number is also not displayed in your account.

Due to this activity, your Amazon.com account has been closed and all open orders have been canceled. To continue shopping with Amazon.com, we ask that you open a new Amazon account. Your order history and other features such as Wishlists cannot be transferred to your new account.

Note the email starts out “Thank you for letting us know about unauthorized activity.” I quickly responded that there was no authorized activity (and I certainly didn’t let them know). Oddly enough there was another email at 9:30AM that morning (AFTER the account closure) suggesting I needed to call to reset my password again. I did call but the customer service agent was only able to offer to send another email to the Account Specialist team.

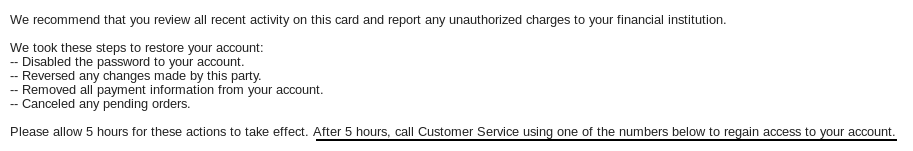

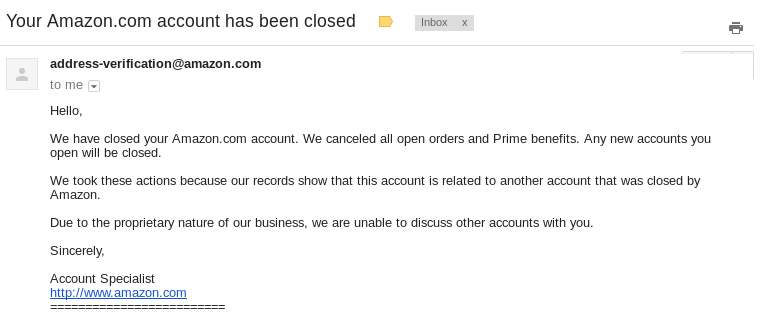

Frustrated at this point, and not wanting my friend’s present further delayed, I dutifully followed the instructions about using another Amazon account, after all Amazon specifically told me that “To continue shopping with Amazon.com, we ask that you open a new Amazon account.” I went into my business account which I had previously used to host AWS instances for various business projects. However, my attempt to complete my order was similarly thwarted. I initially received an email to confirm my billing address, which I quickly replied. I was then presented with this sternly worded email:

“Any new accounts you open will be closed.”

So, despite having told me previously to open a new account to continue shopping, Amazon has decided they will close any account I open in the future, with no discussion of why this was occurring, no information as to what led to this decision and no opportunity to dispute or appeal it. Some faceless, nameless, bureaucratic Account Specialist had declared me persona non-grata. Assuming the Account Specialist is even a person and not a bot.

My virtual death as an Amazon customer.

Quite a few of the most recent complaints on BBB for Amazon are about inexplicable account closures. Luckily, my dependence on Amazon is negligible. Though I’ve been a customer 10 years, I wasn’t using AWS actively and canceled Prime just a few months ago because it wasn’t worth the costs. However, I could only imagine how this could have affected me. Having dinner the next day with a friend in the privacy/security industry he was shocked and concerned because he orders virtually everything off Amazon as I know many do. What if I used Kindle, would I lose all my purchases? I’d be more concerned about those who’s livelihood depended on the Amazon service. What if I was an associate and depended on Amazon referrals for this blog’s revenue? Or a reseller on Amazon? What I had had extensive use of AWS for my business? Perhaps if I was in one of these categories they would have been more circumspect in their closing my account. Perhaps I would have had another avenue to escalate, but as a regular consumer I certainly didn’t.

As for my particular circumstances, first and foremost, I’m a bit miffed that I can’t get my order history and wish-lists. I have frequently referred to my order history when doing my year end taxes as some of my purchases are business related. Also, I’ve spent years adding things to my wish-list, mostly books that I’ll probably never get around to ordering, though I have had relatives order them occasionally for birthdays in the past. There is no way for me to reconstruct this information. Account closure seems particular vindictive. Of course, I don’t know why they closed my account, so it’s hard to say. I can only guess that they suspected some sort of fraudulent activity despite all the charges to my account having always gone through and never disputed. If potential fraud is the reason, they could have suspended ordering privileges, but allowed the account to still access historical data. One problem with behemoths such as Amazon is that by providing multiple services to which people may become dependent, a problem in one area can have an out-sized impact on the individual. Segmentation of services is important in reducing risks. A problem with my personal account shouldn’t affect my business account. A problem with ordering physical products shouldn’t affect my Prime video membership or Kindle e-books. A problem with my use of the affiliate program shouldn’t affect my personal use as a shopper. Etc.

Were I in the EU, I might have some additional recourse under the newly passed GDPR. Namely

- Under Article 15 I could receive the personal information they have on me, including not only my wish-list and order history, but potentially whatever information was the basis for the account closure.

- Under Article 16, I could potentially rectify any inaccurate data about me which may have lead to the decision to close my account.

- Under Article 20, the right to data portability. While this probably doesn’t apply to my order history, since it’s arguable whether I “supplied” the information, it would apply to my wish-list, since that subjective preference data is something I supplied when I clicked “Add to my wish-list”

- Under Article 21, the right not to be subject to automated decision making. More specifically:

the data controller shall implement suitable measures to safeguard the data subject’s rights and freedoms and legitimate interests, at least the right to obtain human intervention on the part of the controller, to express his or her point of view and to contest the decision.

Of course, I don’t know if the account deletion determination was based on an automated decision, but I suspect in part, they have some AI making a determination at some point to suspend or restrict use of my account.

Once it’s available, I’ve been considering applying for Estonia’s digital nomad visa. If I still care at that point, when I’m in the EU, I might subject Amazon to some of these rights to which I’m not afforded as someone in the US. It’s highly likely I won’t care at that point. As I stated, my use of Amazon, unlike many associates of mine, has been limited. Maybe my account closure is a good thing as it pushes me closer to removing my reliance on the big tech firms. I’ve closed my Facebook account and haven’t used Facebook in almost 6 months (though to be transparent, I still use Instagram). I moved several years ago to a Libre 15 by Purism running PureOS (an Ubuntu Linux variant) and away from Windows, though again in full transparency, I purchased a Microsoft Surface Pro for presentations (on newegg, btw, where I’ll obviously be shopping more from now on). At least Microsoft is more in the pro-privacy camp. I’m still trying to extricate myself from Google. I purchased an iPhone (again on newegg) for the first time having been an Android user for many years. I’m still, unfortunately, on GoogleFi because I like that it works when I travel internationally. I still use Gmail for my personal email, though not for business anymore, having my own domain. One reason I still use Gmail is when I have to give my email address to someone orally, I know they aren’t going to misspell gmail.com like they might privacymaverick.com.