I’ve been thinking a lot about Mesh Networking and the possibility to foil NSA style tapping by bypassing centralized networks for localized networks. For those who don’t know mesh networks are ad-hoc peer to peer networks, primarily wireless. The decentralized nature of the communications provides some level of privacy. Additional privacy comes with making the system anonymous. However, it seems that anonymity comes with a price to bandwidth. Here are some of my findings:

The standard model is circuit switched. In other words, each node maintains a topological map of the entire network, so that it knows who is connected to whom. This allows it to create a circuit through the network to the destination. That means that each transmission takes t bandwidth where t represents the size of the data. If s represents the shortest number of hops from source to destination then the total network bandwidth used B= s*t. In this model, no storage is required because each node forwards the data without need to retain it. There is some data storage requirements for the network map. This map grows with n^2.

Circuit: (Bandwidth = s*t, Storage: n*(m*n)^2) m= the amount of data necessary to indicate a link or not (maybe a bit, maybe a byte if you store strength).

The upside is that each new node increases the bandwidth of the network. The downside of this is that an attacker could possibly follow the data as it gets transferred from node to node and identify sender and receiver, providing linkability and thus defeating anonymity.

Consider, alternatively a broadcast model. In this model, no topological map must be stored but every node gets a copy of the data.

Broadcast: (Bandwidth = n*t, Storage: n*t)

In this model, nobody can identify the destination of a message which is very privacy preserving. However, the bandwidth cost are enormous. Now, each new node added to the network actually adds an external cost to the other node, similar to a car being added to a highway. The storage cost also increase at rate n*t because every node must keep a copy of the message (or at least a digest) for a period of time to prevent it re-accepting the data from one if it’s neighbors.

A third option is the random walk model, also called the hot potato. A node passes the data packet to another who passes it again, etc. In this model no node keeps a copy of the data once it has passed so the storage costs are 0. The bandwidth is a minimum s*t, because that’s the shortest circuit. BUT, the packet could be passed along for ever, so the bandwidth could be potentially infinite. Needless to say this is not good.

Random walk: ( S*t < Bandwidth < ∞, Storage = 0)

What about a biased or intelligent random walk, a lukewarm potato. The network has the following rules. Each node ask its immediate neighbors, “is this yours?” Appropriate response are “yes, give it to me” “no, but I’ll take it” or “no, i’ve seen it”. If the neighbor said yes, the node gives them the data. If the neighbor say “no, i’ve seen it” it ignores that node. The node then randomly selects one of the nodes that hasn’t seen the data and sends it to them to continue the process. If the node can’t find anybody to hand it over to, it tells the node that it got it from that it can’t pass it along, that node starts over again. [Alternatively, it could force one of the nodes that have seen it to take it again]. This method allows the data to snake it’s way through the network but not repeat any nodes. Here is the bandwidth and storage boundaries.

Intelligent random walk: ( s*t < Bandwidth < n*t, s*n < Storage < n* t)

So this doesn’t have as low of bandwidth and storage as the circuit but it’s not as bad as broadcast for storage and not as bad as random walk for bandwidth. However, anonymity is not perfect. An attacker who had access to the entire network could identify the recipient as the packet traces it ways through the network.

It appears then than anonymity costs either in bandwidth or storage cost. The question is what is more valuable to the network. There maybe additional techniques to mitigate this, and I continue to investigate this area.

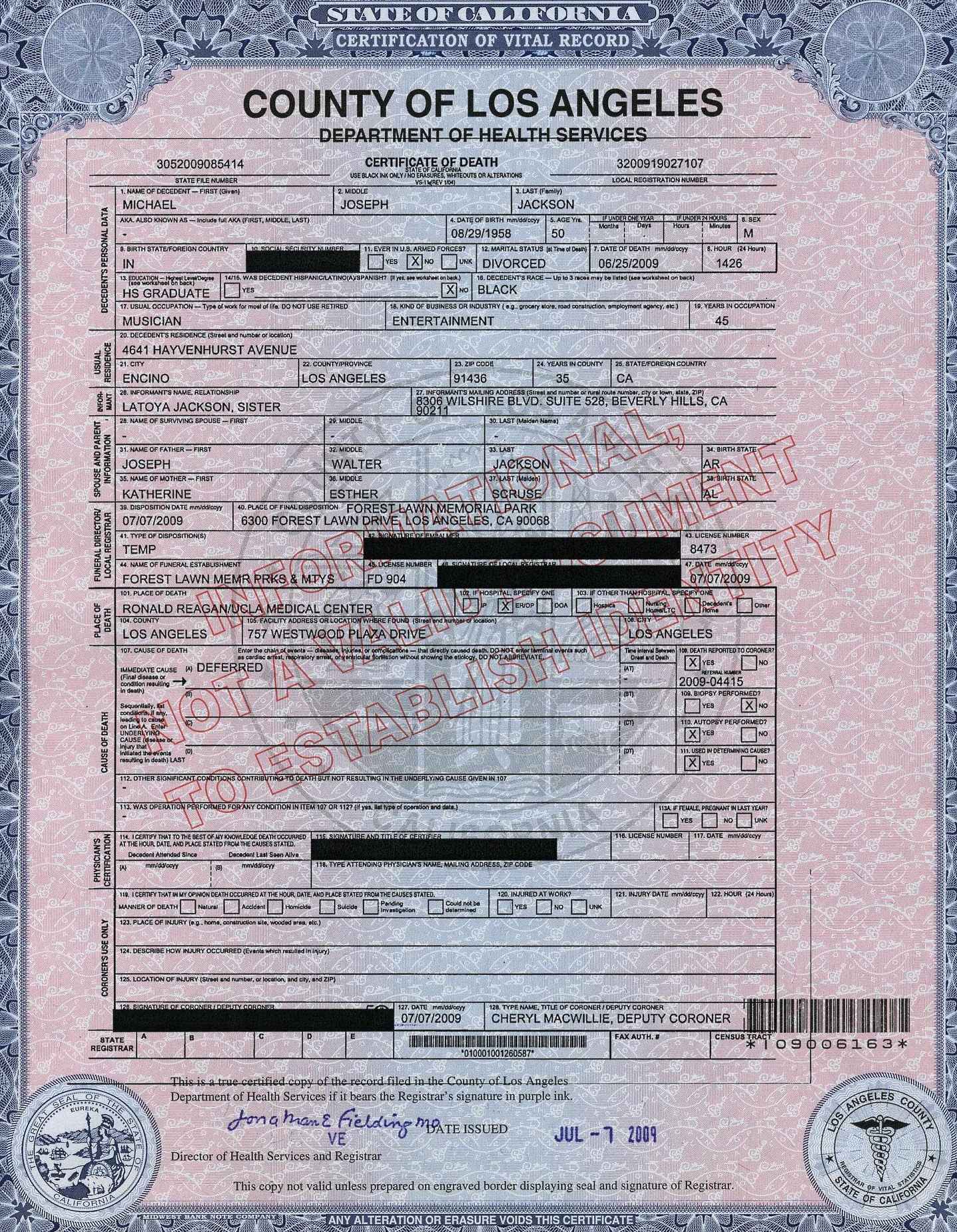

Fast forward to 2013 in which I’ve had a few friends, unfortunately, pass away recently. One friend’s death was particularly gruesome and was publicized in the local press. The other friends were more mundane and to this day I don’t know what they died of. One of those was elderly and I suspect due to health issues, though I’m unsure. The other friend was my age. In Florida, a death certificate is public record an easily obtained by paying the appropriate fee. However, only certain related person or those with an interest in the estate of the deceased may receive a death certificate which list the cause of death. I believe that this is fairly common practice through the US. I have witness that it is generally verboten to ask or tell if known, what one’s cause of death is unless it is widely known (obvious illness, accident, murder, etc). It appears that we have adopted a cultural norm against generalized disclosure of cause of death and that norm has been codified in law as they related to death certificates. This isn’t airtight (as certain causes mentioned above become widely known) and it doesn’t appear to be based on any preference of the deceased, though one could imagine the deceased leaving instructions to publicize their cause of death.

Fast forward to 2013 in which I’ve had a few friends, unfortunately, pass away recently. One friend’s death was particularly gruesome and was publicized in the local press. The other friends were more mundane and to this day I don’t know what they died of. One of those was elderly and I suspect due to health issues, though I’m unsure. The other friend was my age. In Florida, a death certificate is public record an easily obtained by paying the appropriate fee. However, only certain related person or those with an interest in the estate of the deceased may receive a death certificate which list the cause of death. I believe that this is fairly common practice through the US. I have witness that it is generally verboten to ask or tell if known, what one’s cause of death is unless it is widely known (obvious illness, accident, murder, etc). It appears that we have adopted a cultural norm against generalized disclosure of cause of death and that norm has been codified in law as they related to death certificates. This isn’t airtight (as certain causes mentioned above become widely known) and it doesn’t appear to be based on any preference of the deceased, though one could imagine the deceased leaving instructions to publicize their cause of death.